Reading. Carrano ch 4.

Computer memory divided into bytes of 8 bits each. (On most kinds of machines.)

Each byte has a unique address. (On most kinds of machine.)

Variables are stored in contiguous bytes.

E.g. on many machines an int requires 4 bytes so bytes 100...103 might contain an int variable x.

Each variable (including objects) has an ``address'' which is the location of that variable's first byte.

E.g. int variable x might have an address of 100.

Pointer values are these addresses

Pointer variables hold these addresses.

Declare two int variables

int x, y ;Declare a pointer variable

int *p ;

Assign p to hold the address of x.

p = & x ; // Assign the address of x to p

Now x can be referred to either as x or as *p

*p = 0 ; // Assign 0 to x y = *p ; // Assign 0 to y

Pointer variables can be reassigned to.

p = & y ; // Assign the address of y to p *p = 1 ; // Assign 1 to y

C++ variables can be classified according to life-time: Static, Stack, Heap.

Static variables exist throughout execution of the program.

Includes any variable declared outside of any function: E.g.

int i = 0 ;

void foo() { i = i+1 ; }

Stack variables exist from their point of declaration until the end of the block smallest block that contains their declaration.

int bar( ) {

int i = 0 ; // i is created here

{ int j = 13 ; // j is created here.

i = i + j ;

} // j is destroyed here

i = i + 1 ;

return i ; // i is destroyed here }

The memory that was used by i might be reused later for some other variable.

Next time bar is called , i might have a different address.

Heap variables are created and destroyed under program control.

Dynamically allocated variables do not have names!

But they do have addresses.

Thus they must be referred to by using pointers

// Declare a pointer to integer.

int *p ;

// Create a new variable and assign its address to p.

p = new(nothrow) int ;

// Assign 21 to the new variable.

*p = 21 ;

// Print 21.

cout << *p ;

Sometimes ``new'' can not create a new variable because there is no more space in the process's memory.

In that case it returns a "null pointer value", written as 0.

One should always check for this.

int *p

p = new(nothrow) int ;

if( p == 0) {cout << "Sorry out of space" ; }

else { *p = 21 ; cout << *p ; }

Coding Tip: The rule of the null check. Always check if the result of a new statement is 0.

Extra Note For each type, T, there is a null pointer written (T*)0.

On most computers, null pointers are represented by a word with all bits equal to 0. Regardless of whether or not this is so, the int constant 0 will convert to a null pointer, which is why we can usually write 0 for a null pointer.

You can also write a null pointer as either (void*)0 or as NULL. But you can only write NULL if some file such as iostream has been included. End Note.

Consider this erroneous program

foo() {

int *p ;

p = new(nothrow) int ;

*p = 21 ;

cout << *p ;

return ; // Mistake: p is destroyed here,

// but not *p

}

In this case, the space taken up by the allocated variable can never be used again.

We have not recorded where it is so the program can not use it.

But the C++ system remembers that it exists and will not reuse the space.

The statement "delete p;'' will

Coding Tip: The rule of equal deletion. For every new executed in your program exactly one delete should eventually be executed to free the space.

Common mistake:

int *p, *q ; // Two pointers. p = new Node ; q = p ; ... delete p ; ... *q = ...

q is called a "dangling reference" or a "stale pointer". The pointer stored in q can not be relied on to have any meaning. The memory locations at that address may have been reused for something else.

Coding Tip: The rule of stale pointers. Never use a variable after it has been destroyed.

Extra Note

Think of allocated variables as being balloons and pointers being strings to those balloons.

new - blows up a balloon and

p = new(nothrow) int ; // p is a string tied to the new balloon.

q = p ; // now there are two strings tied to the balloon.

p = 0 ; // now only one.

delete q ; // pop the balloon.

The rule of the null check: Check that there is a balloon at the end of your string.

The rule of equal deletion: If you let go of all the strings, your balloon will float to the ceiling. You can never reach it, but it will continue to take up space. So you should pop ever balloon.

The rule of stale pointers: Never use a popped balloon. End Note.

A special notation is used for data members of structures and objects

class Pair { public : int left, right ; } ;

pair *pairP = new(nothrow) Pair ;

...

... (*pairP).right ... ;

The notation (*pairP).right means the "right" member of the pair object that pairP points to.

To save a bit of typing, we can right pairP->right .

In general, if p is a pointer, then p->f is an abbreviation for (*p).f

"struct" exactly the same as "class", except that all members are public by default.

So can also write:

struct Pair { int left, right ; } ;

instead of

class Pair { public: int left, right ; } ;

Using dynamically allocated variables we can create very interesting structures.

Consider a class

struct Node {

int data ;

Node *next ;

} ;

We can use a pointer to such a class to represent a sequence of integers.

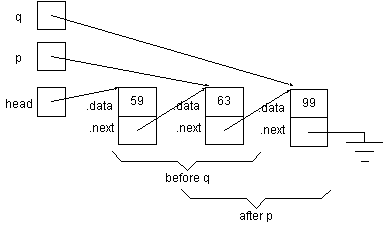

Suppose head is a pointer to Node.

Linked List: We call such a collection of structures, a "linked list".

Links: Each pointer variable in the linked list, we call a "link". Thus the links of the list in the last picture are

head, head->next, head->next->next,

and head->next->next->next

In general, a linked list with n members will have n+1 links.

Head and Tail:

After, Before, and Between:

[In this section I will ignore the rule of the null check to keep examples simple.]

Assume variable head is the head link

We will use a pointer variable p to keep track of the position in the list.

We will use an int variable len to count the nodes.

Loop Invariant:

[A "loop invariant" is a description of the state which we expect to hold true at the start of each loop iteration, and also when the loop has terminated. For a short discussion of loop invariants and their use in designing loops that work see Invariants 101.]

When we no longer need a list, we should delete all the nodes of a list.

Here is an algorithm to do that.

Variables

Invariant:

We will build a list consisting of a sequence of numbers entered by the user.

Variables

Invariant:

Variables

Invariant:

© Theodore S. Norvell 1996--2004.